|

If you are one of the 10-15% of people who claim they don’t procrastinate, stop reading and go and do whatever you’re avoiding! Anyone else, congratulations on your honesty! That’s a good start. What we tell ourselves Here’s how it works with me. Tasks I procrastinate over are typically big (grant applications, papers), boring (administration), or not obviously beneficial to me or my team (reviewing). The conversation in my head starts: “I must get on with this, I’m feeling really guilty holding someone else up”. Or: “If I don’t start soon, I’ll end up super-stressed doing it at the last minute, so why can’t I just do it?”. The answer comes back: “I need a clear mind first and I won’t have that until I’ve got these other niggling tasks out of the way. Otherwise, I’ll worry about people chasing me for them”. Or: “I’m here to do science, not administration. Filling in that form is just depressing!”. How about you? Similar thoughts? Others?

0 Comments

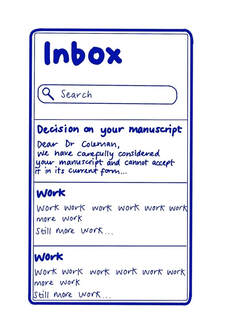

“Terrifying!”. That’s the word I hear most from ECRs considering a tenure track job offer. They, like most of us, once sat in a PhD interview saying this is exactly what they wanted. So what explains this reaction when it becomes reality? We all find something scary. I feel it when chairing a meeting or pursuing a big new opportunity. Many people, inside and outside science, fear public speaking. And whose heart doesn’t beat faster on reading the email subject line “Decision on your manuscript”? Why? And what does it do to us? We love science but not the stuff that comes with it: all those events that trigger anguish, insecurity, overwhelm and frustration. The failed experiments, short-term contracts, spiralling administrative demands and reviewers who just don’t seem to get it. How can we keep a clear mind with all that going on?

|

AuthorProfessor Michael Coleman (University of Cambridge): Neuroscientist and Academic Coach: discovering stuff and improving research culture ArchivesCategories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed